Article and photos by Seeger Gray

A bilingual profile of Daniel Cano, a chef who's stepping back from the ring after 17 years of wrestling as a luchador in the Chicago area.

Daniel Cano poses for a portrait in his Primo Loko luchador outfit and Santa hat outside his home in Westchester, Illinois on November 17, 2023.

The luchador Primo Loko prepared for his final Chicago Style Wrestling battle royal like it was any other – by cooking up a feast.

Daniel Cano whirled from dish to dish, chopping chicken he’d marinated for a week and spontaneously dipping strawberries in white chocolate and cookie crumbs. Coolers and trays wrapped in plastic stacked up in his home in the afternoon before the show.

He said he’s cooked for his “wrestling family” for free for years, a way of giving thanks.

“For me, wrestling was always a safe haven,” Cano said. “I earned the title chef. I earned the title pro wrestler. So I like to live up to it every time.”

But the afterparty Cano was planning was also a bittersweet farewell to Chicago Style Wrestling and a step back from being a luchador – for his health and his career.

Daniel Cano prepares food with help from his mother at his home in Westchester, Illinois on November 17, 2023.

Daniel Cano drizzles melted white chocolate onto strawberries coated in cookie crumbs at his home in Westchester, Illinois on November 17, 2023.

Daniel Cano sweeps the kitchen floor at his home in Westchester, Illinois on November 17, 2023. A photo and a drawing of Cano and his brother as children hang on the wall.

Cano’s wrestling journey began when he was a child growing up in Cicero, Ill.

“Everybody pretty much was a fan in my family,” Cano said. “Me and my grandfather, our favorite match was the battle royal.”

He jumped at a chance to step into the ring in 2006 at a Windy City Pro Wrestling “fantasy camp” – a three-day boot camp for aspiring professional wrestlers to develop both their physical skills and their personas.

When his original plan for a character fell through, Cano recalled getting the idea for Primo Loko from mass deportations in Chicago’s Latino neighborhoods.

“They were throwing busloads of people on buses and shipping them off to Mexico,” Cano said. “I was like, ok, I got it: I’m going to be an immigrant, I’m going to be Primo Loko. And my thing is I’m coming back to America, and I’m going to earn my citizenship by beating the shit out of everybody at Windy City Pro Wrestling.”

For a bit of humor, when asked if he’d been deported to Mexico, Primo Loko would reply, “What? I’m from Canada!”

Photos of Daniel Cano with his brother and his mother within a larger display of family photos, pictured at Cano's home in Westchester, Illinois on November 17, 2023.

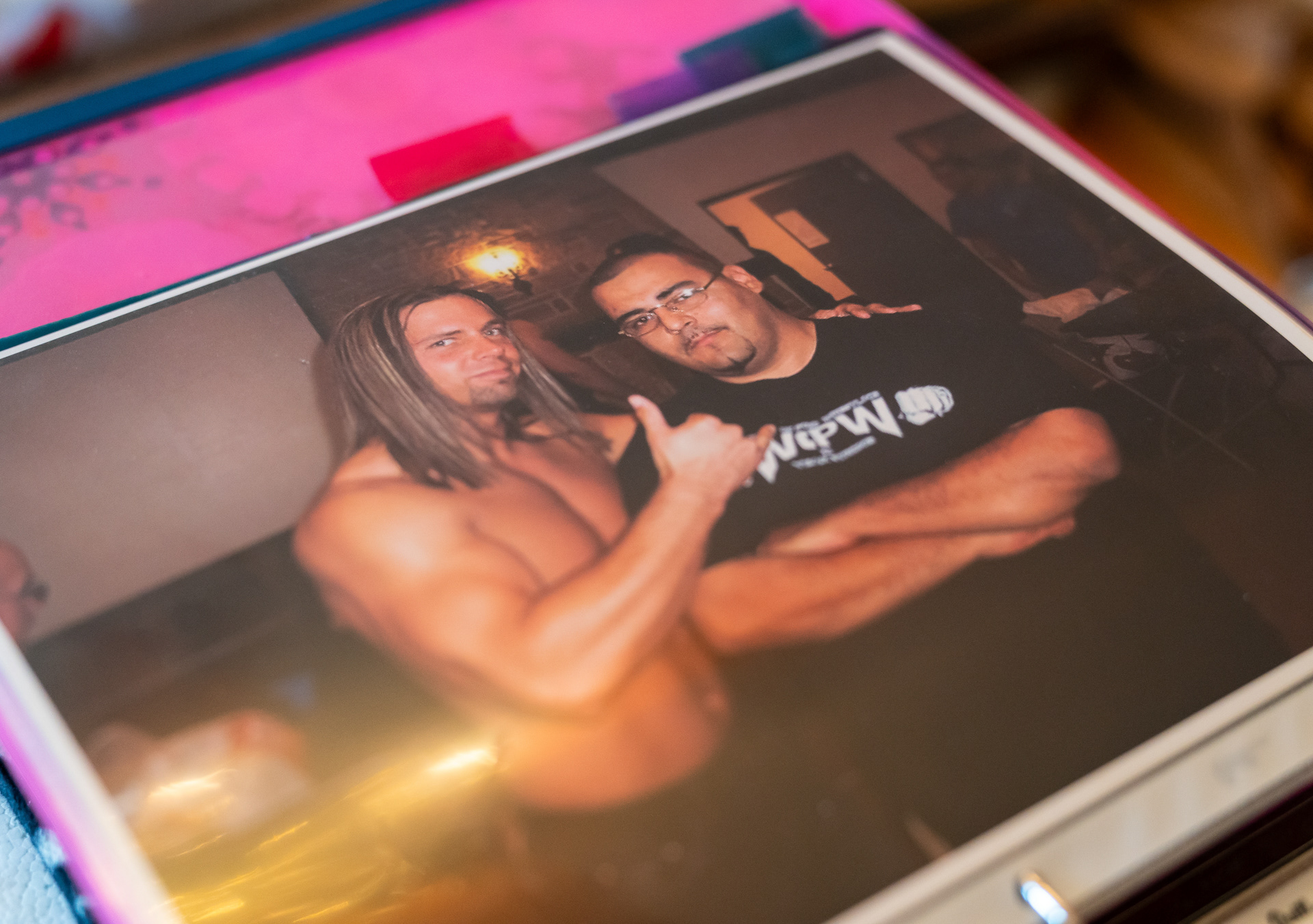

A 2007 photo of Daniel Cano, right, and Steve Boz, his mentor in Chicago Style Wrestling, pictured in a binder at his home in Westchester, Illinois on November 17, 2023.

Cano has been a luchador since 2006, all while working primarily as a chef. Sometimes, his two careers go hand in hand.

On Oct. 22, Cano catered a meet-and-greet with five luchadores before their matches at Cicero Stadium for IMPACT Wrestling.

“They asked if I would be able to cook that Latin-style menu. So it was more than just a fan meet-and-greet. It was something I worked my whole life for,” Cano said. “It was just so cool to celebrate the history of lucha libre.”

Daniel Cano listens to Laredo Kid while serving food at a luchador meet-and-greet before IMPACT Wrestling's show at Cicero Stadium in Cicero, Illinois on October 22, 2023.

Juventud Guerrera, Laredo Kid and Black Taurus celebrate in the ring after winning their match against The Rascalz during IMPACT Wrestling's Bound for Glory Fallout show at Cicero Stadium in Cicero, Illinois on October 22, 2023.

“When they called me, I didn’t know who was coming. But then when they put the flier out, they announced it on social media, I saw they were bringing in Konnan and Juventud. I couldn’t believe it,” Cano said.

While not all of his catering work is for wrestling organizations, Cano said the jobs he finds through connections in wrestling are particularly meaningful.

“In one year, I got to cater for WWE, AEW and IMPACT Wrestling. And that’s a hell of an accomplishment for me,” Cano said.

Chicago Style Wrestling is smaller than those national wrestling organizations and wasn’t paying Cano to cater. That didn’t stop him from going all out for one last feast.

In the afternoon of Nov. 17, hours before the show began, Cano arrived at the American Legion Post 974 in Franklin Park, Ill., a frequent venue for Chicago Style Wrestling shows.

He set up some of the non-perishable dishes and decorated the back room with Christmas lights, wrapping paper and candy canes. Then he brought the early holiday cheer outside.

Daniel Cano looks at himself with a small mirror as he puts on a fake beard at the American Legion Post 974 in Franklin Park, Illinois on November 17, 2023.

Daniel Cano, wearing his luchador mask and Santa Claus outfit, gives a present to Kallie Winters, 8, before a Chicago Style Wrestling show at the American Legion Post 974 in Franklin Park, Illinois on November 17, 2023.

Cano’s love for lucha libre has kept him wrestling since 2006, but at 41 years old, he said he’s “been ready for a couple years to stop doing this.”

Cano has struggled with concussions over the years, though he said none happened while wrestling. However, he said head injuries have made him more nervous about being in the ring.

“I can’t hear out of my right ear. And in wrestling, you’ve got to be able to hear everything. You’re communicating while you’re wrestling,” Cano said.

He said people with concussions don’t always know when to call it quits, a problem that remains in the professional wrestling world.

“A lot of wrestlers have had more than I have, and they’re still on TV wrestling. I don’t know how,” Cano said. “I have learned that every head injury I’ve had after my first concussion, it’s gotten worse and worse and worse.”

“I’m getting to an age where I don’t mind sharing my story, because, well, maybe someone can learn from it,” he said.

Daniel Cano grapples with another wrestler as Primo Loko in a Chicago Style Wrestling battle royal match at the American Legion Post 974 in Franklin Park, Illinois on November 17, 2023.

Cano didn’t spend much time in the battle royal that evening. Primo Loko entered a ring packed with wrestlers, grappled with a few and was soon thrown over the ropes. He walked off, waving to the crowd with his head held high.

“I was just trying to live my dream. That was my goal, to be in one battle royal in front of a big crowd,” Cano said. He estimates he’s fought in at least 50 by now.

But it wasn’t goodbye just yet. While other matches continued, Cano rushed home to pick up the rest of the food for the afterparty.

Daniel Cano jokes around with his friend Kimmy Zilla, another Chicago Style Wrestling wrestler and wife of Steve Boz, who mentored Cano in the organization, while setting up a holiday-themed afterparty at the American Legion Post 974 in Franklin Park, Illinois on November 17, 2023.

Daniel Cano prepares a tray of salad with homemade pico de gallo before a holiday-themed Chicago Style Wrestling afterparty at the American Legion Post 974 in Franklin Park, Illinois on November 17, 2023.

As the show wrapped up, wrestlers, friends and family trickled into the back room of the American Legion Post 974. One asked Cano, “Why do you spoil us?” before filling his plate.

Daniel Cano poses for a selfie with his friends Linda Coulson, left, and Kimmy Zilla, another Chicago Style Wrestling wrestler, at a holiday-themed afterparty he prepared food for at the American Legion Post 974 in Franklin Park, Illinois on November 17, 2023.

Daniel Cano leaves the American Legion Post 974 after wrestling in a Chicago Style Wrestling battle royal match to pick up food from his home for a holiday-themed afterparty in Franklin Park, Illinois on November 17, 2023.

“I learned in culinary school, as long as you’re still alive, you can always do better. And that’s why I strive every day to be just the best me. No pressure, no stress,” Cano said.

###